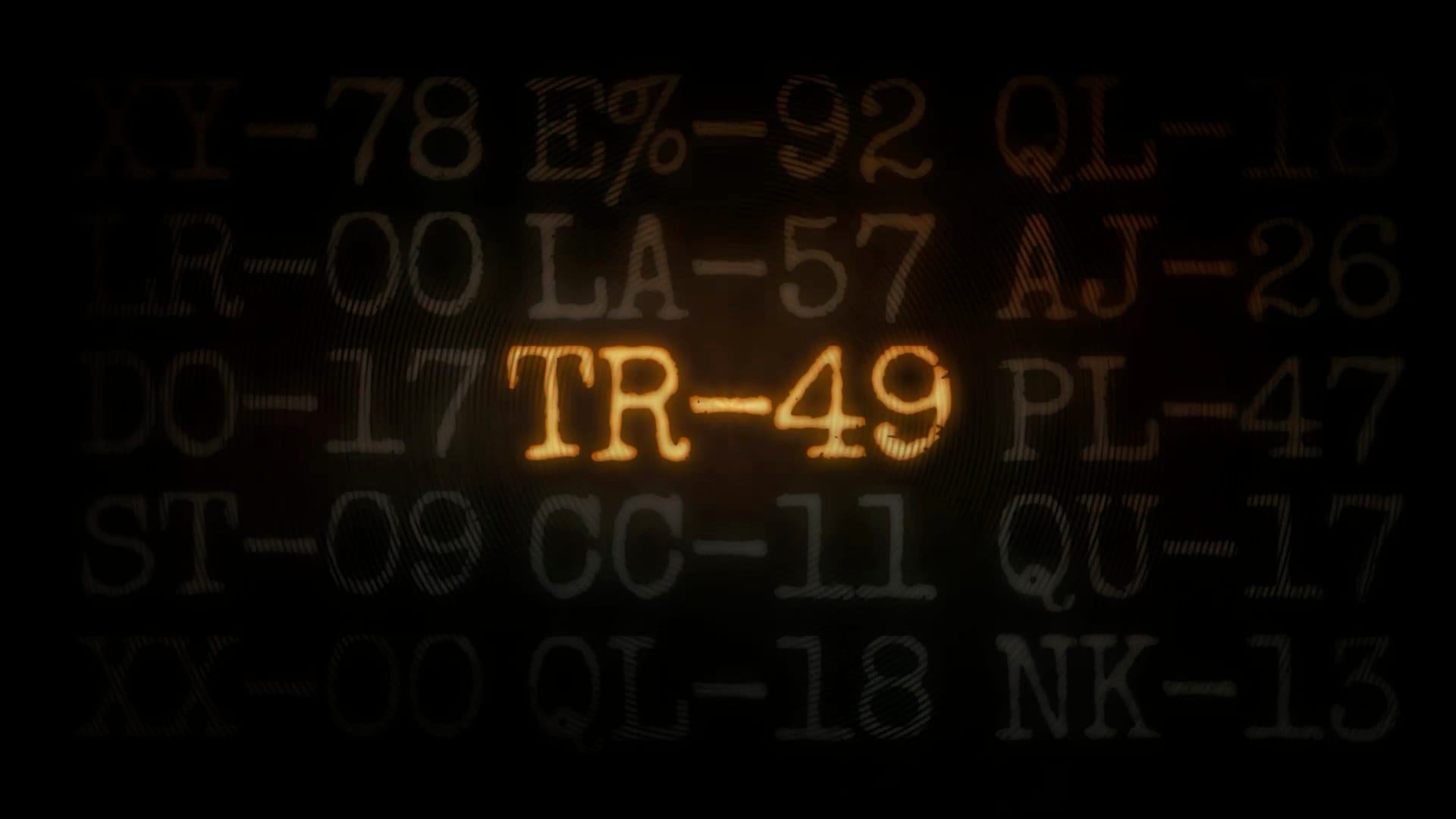

An interview with TR-49 writer and director Jon Ingold

inkle's co-founder on storytelling and being an indie studio

I've already called inkle studio's TR-49 an early contender for my Game of the Year. It's a game where your interactions with the world and even your interactions with the story are severely limited, but it still pulls off a complexity and depth of world-building that hasn't really left my head since I finished it.

I reached out to the game's writer and director — and co-founder of inkle studios — Jon Ingold to talk about it. He graciously agreed to an interview.

No edits were made to this interview — I didn't even correct the British (wrong) spellings.

TR-49 is all about stories, both the text and the people who tell them. In the game, the creators of the machine throw in some of the classics to round out the computer’s data. What are the books you’d add?

We added them already! There's about thirty real books in there. (I meant to do more, but I figured that more obscure ones would never get tried by anyone.) It's a shameless list of mainstream books that I think matter - Orwell, Christie, Chandler, Wodehouse, Tennyson, Tolkien. But books are funny; they go deep into your head but you still forget about them. I forgot to include Thomas Mallory's La Morte d'Arthur, or The Dark is Rising, or the Wizard of Earthsea, or even T. H. White's The Once and Future King. Madness. I might patch that last one in.

You’ve written and published short stories and a novel on top of your video games. What’s different about how you approach telling stories in a narrative game format as opposed to more traditional writing?

Game writing is easier. Controversial, maybe, but, I find, true. I'll tell you why - you can hand off some of the pacing decisions to the player, while pacing in linear fiction is the single hardest thing. Yes, this moment needs to happen, but exactly when? Now, a little earlier, a little later? What ripple effect does that have if I change it? This stuff keeps novelists awake at night. In a game, you stick it behind a choice and the player can do it when they feel like it: and if it doesn't quite work there, then that's at least partly the player's own fault.

Similarly, for editing: the adage in linear writing is "kill your darlings". For our more branching games, the adage is "just write everything". All the content goes in, and then we just stir it around until it sits right.

Oh, and one more thing: in linear fiction, the protagonist needs a sensible reason not to just give up at every single moment of the story. In a game, players will "go over there" simply because the level geometry exists, and they can stumble on the hook when they get there. When I converted Heaven's Vault into a two-part novel series that was the biggest hurdle: exactly why is Aliya going to this moon she's just discovered? Why doesn't she just sit back, have a cup of tea, and a little sleep? Games just don't give you a button to do that.

The music in your inkle games stood out to my partner — she's the classical music buff. She picked out Rhapsody in Blue and Scheherazade, for example. Did you pick the music in your role as (co)director? Was there a reason for those choices?

For a lot of our games, we get original music composed. We always hire Laurence Chapman: I genuinely think he's a generational talent, and I absolutely adore all the work he's done for us - from the majestic Heaven's Vault score to the short, mechanical loops of TR-49.

For the two Overboard! games, though, we decided to go with found and copyright free music, for a historical and eclectic feel. The choices are serendipitous - driven mostly by what's out there and usable - but that being said, we wouldn't have settled on the approach if I hadn't found a copyright-free recording of The Flight of the Bumblebee, which is the perfect signature riff for Overboard! (and finding jazz cover of it for Expelled! was a real bonus.)

There’s a theme of powerlessness in several of the inkle games, including TR-49 — specifically female characters trapped in powerless and controlled or controlling situations. Can you speak to the choice to make these characters who they are?