Cyberpunk 2025: Lowlife and high-tech

What does cyberpunk even mean?

Ultimately, I want to get this series to a place where I can just write about one piece of media at a time and draw parallels to 2025. I don’t think we’re there yet, though, because there’s a little more foundation to lay. Specifically, what the word “cyberpunk” even means. I can point to it as an aesthetic. I can even identify it as a genre. But I don’t have a good grasp on its origins or its (implicit) goals.

In the preface to William Gibson’s Burning Chrome, Bruce Sterling, another author we’ll come back to at some point, describes Gibson’s writing with some flowery prose. Gibson didn’t invent the genre of cyberpunk, but his work had a heavy influence on the genre generally (and, indirectly, on Cyberpunk 2077), so it’s worth starting with him here.

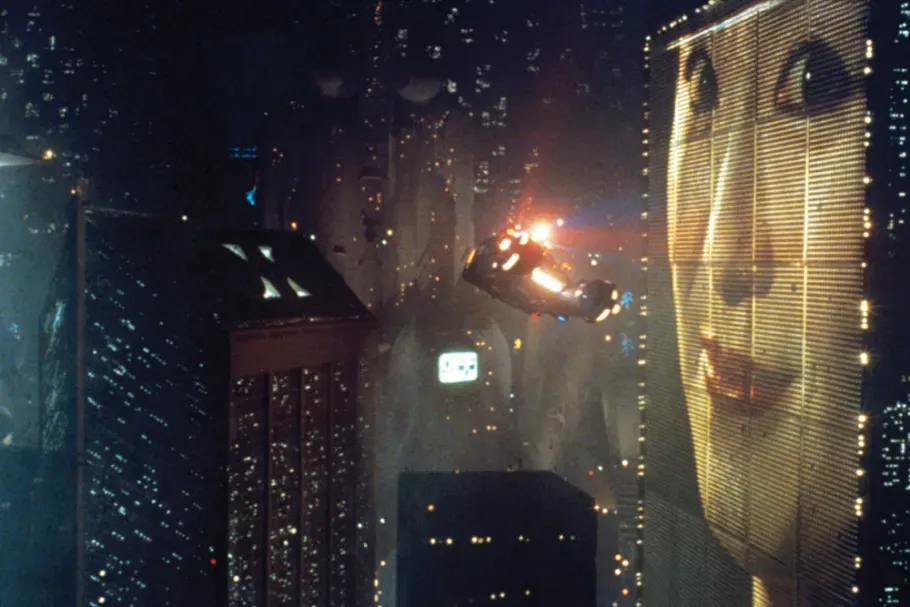

As Sterling says, Gibson’s stories deliver a “one-two combination of lowlife and high tech” and “his characters are a pirate’s crew of losers, hustlers, spin-offs, castoffs, and lunatics. We see his future from the belly up, as it is lived.”

The writing is “an instantly recognizable portrait of the modern predicament. Gibson’s extrapolations show, with exaggerated clarity, the hidden bulk of an iceberg of social change. This iceberg now glides with sinister majesty across the surface of the late twentieth century, but its proportions are vast and dark.”

Retrofuturism

It’s impossible to discuss cyberpunk (or even punks) without talking about the 70s and 80s. As William Gibson puts it, “you can’t draw imaginary future histories without a map of the past.” Visually, the (early) 80s define the cyberpunk aesthetic, and the society and societal ills of the decade define much of what the genre seeks to confront.

In the decades following World War II, the Western world went through a period of economic growth. In France, this era was known as the Thirty Glorious Years. In the US, we created PBS. Early childhood education was federally funded [Ed. note: Can you even imagine in 2025?]. Jim Crow laws were defeated (for a while, at least). Through the 60s, the average family income in the US doubled.

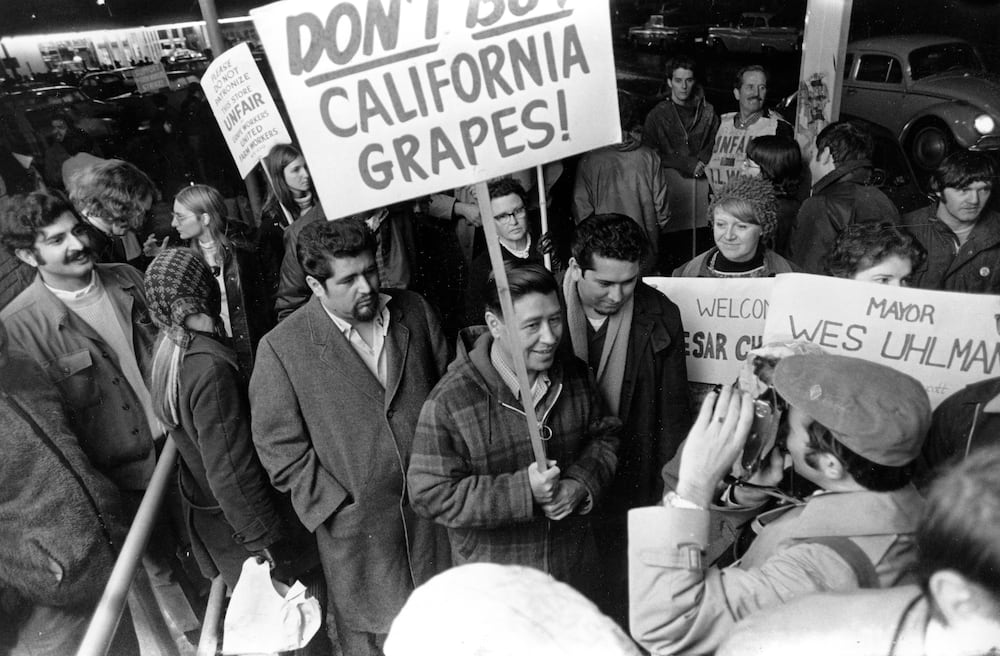

Over the same time period, the global population had almost doubled (hence the name “Baby Boomers”). Rural flight had continued rapidly, with every US state tipping over into majority urban living. Working class exploitation increased along the economic prosperity, leading to strikes like the Delano Grape Strike and the Salad Bowl Strike in California. The Cold War escalated, the war in Vietnam dragged on, President Kennedy was assassinated, Nixon was elected, Watergate happened.

In 1972, an oil embargo against Israeli allies by the Middle East's major oil producers led to the first of two oil crises. The cost of oil and gas increased by 300%, leading the US into its first ever stagflation and the rise of neoliberal capitalism. In 1979, the overthrow of a CIA-backed regime in Iran led to another energy crisis with an even steeper increase in oil prices.

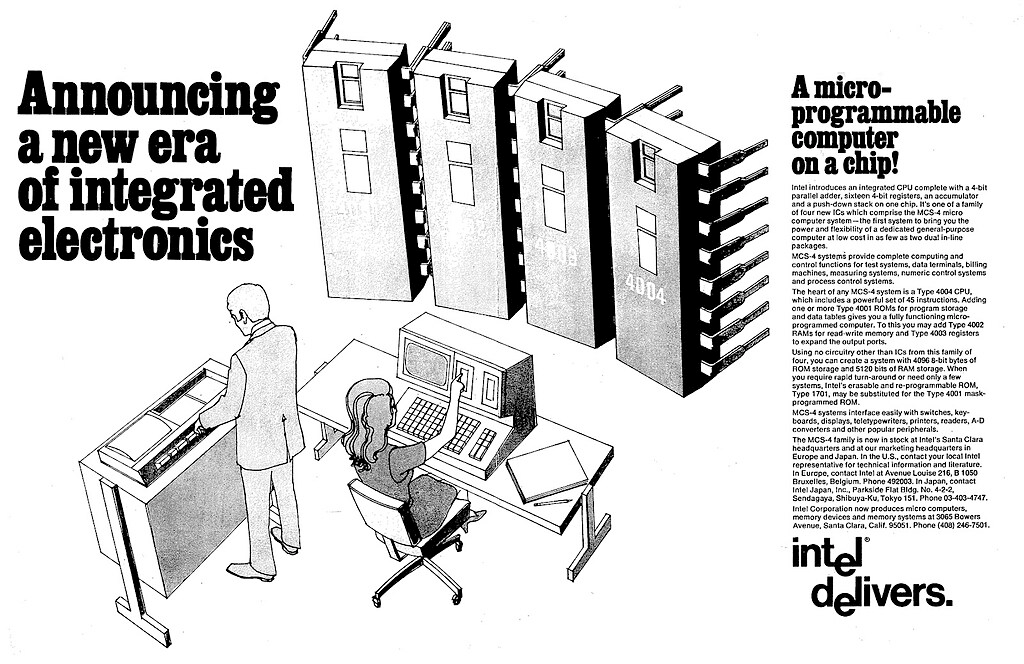

The first commercially available microprocessor was introduced in 1971. The Intel 4004 ushered in the possibility of single-chip computer processors and home computing. By 1977, we had the Apple II.

In 1979 and 1980, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were elected [Ed. note: OOF.].

Where the counterculture of the 60s was disaffected with the status quo, the punks of the late 70s were more existential. To paraphrase one of my favorite climate scientists, a fashwave meme, Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, and Denzel Washington, apparently: “The world you think you live in no longer exists.”