Cyberpunk 2025: One rotten girl in the city of the future

Part 3: The Girl Who Was Plugged In by James Tiptree, Jr.

Before I begin, special thanks to Kay Smith for a sensitivity read and additional research for this article.

I know I keep threatening to direct this series back to Cyberpunk 2077 at some point, but I’m just not there at the moment. Part of it is that there are too many new games to play (like Outer Worlds 2). Part of it is that I just don’t want to play Cyberpunk 2077.

And another, more depressing part of it is that the news is just a constant deluge of cyberpunkian, dystopian headlines.

The DOCTOR is in

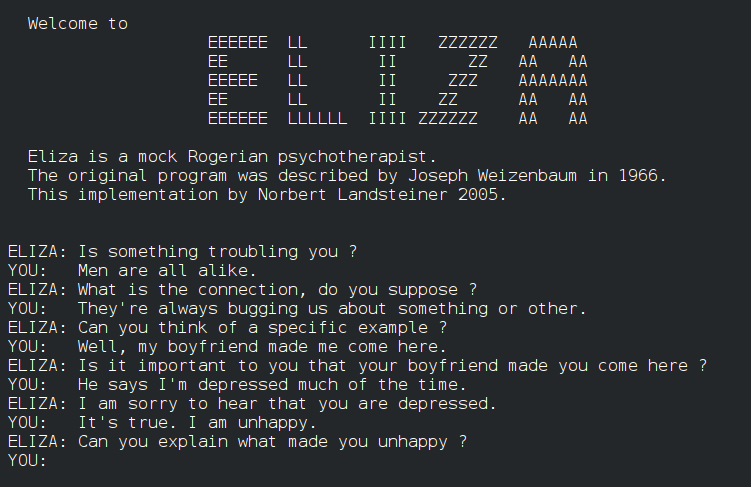

In the late 60s, a computer programmer at MIT named Joseph Weizenbaum wrote ELIZA. ELIZA was a pattern-matching program that could simulate the rules of language and have (text-based) conversations with a user. A chatterbot.

Both ELIZA and its offshoot, DOCTOR, were mock therapists, but all they did was reflect words back, often as a question. If you told it you were depressed, it would respond, “Why do you think you’re depressed?”

ELIZA and DOCTOR were not large language models. They were bare-bones conversation simulators looking for the basest context that could be used to generate a response. But they laid the foundation for what would come half a century later.

Spicy autocomplete

Let’s get one thing out of the way right now: we do not have artificial intelligence in 2025. And we certainly don’t have anything close to the AIs we see in cyberpunk stories like Delamain in Cyberpunk 2077. (There. Mentioned.)

Large language models like ChatGPT 4o, Copilot (which is ChatGPT), Gemini, Claude, and Grok are generative AI. That’s a specific kind of AI and is decidedly not artificial general intelligence, which is something closer to a human (or even, more broadly, animal) intelligence.

Generative AIs communicate (“communicate”) via text, so they are trained on vast amounts of text — stolen text in most (all) cases. All of that text is digested, catalogued, and correlated into mind-boggling weight tables. Super simplified: if presented with the sentence fragment, “The quick brown fox … ,” those weight tables will show that, say, 99.9% of the time, the next word is “jumps.” The LLM doesn’t know what a fox is. It doesn’t know what jumping is. It doesn’t know that the sentence is a pangram. It knows that the word pangram is heavily weighted in association with “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog,” so it can say that it’s a pangram, but it doesn’t know it. The word association game it’s playing is orders of magnitude beyond human capabilities (or comprehension), but it’s hollow.

This is also why LLMs tend to hallucinate. They know what a citation, court case, or factoid looks like, but they don’t know that those are actual things with meaning.

Generative AI is not just a spicy autocomplete (as, I’ll admit, I am guilty of saying). They use a lot more context than autocomplete and can simulate language basically flawlessly. But they’re still not intelligent.

This is what researchers showed in a paper last month. They compared the behavior of humans against LLMs in a simulated environment (click buttons, something happens, test to see if the clicker understands why something happened). It was not a complicated test, and humans “achieve[d] near-optimal scores” with less randomness in their behavior. Humans outperformed the computers across the board and it wasn’t even close.

LLMs have the words, but they don’t have the meaning.

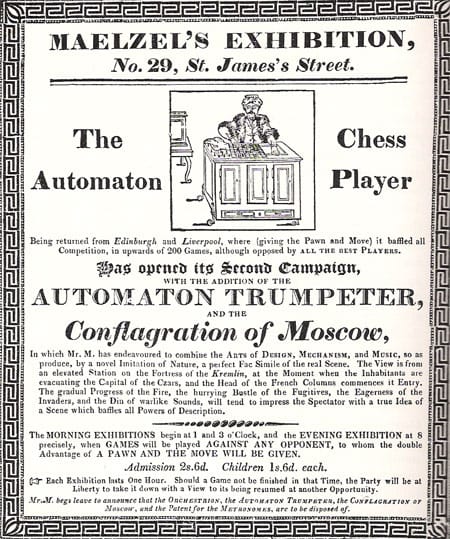

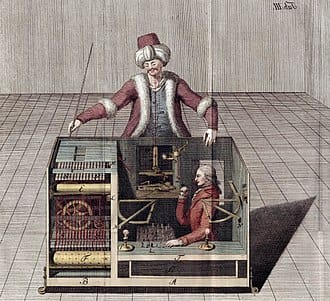

The Mechanical Turk

In the late 18th century, Wolfgang von Kempelen invented a clockwork automaton that could play chess. The mechanism was a small wooden cabinet full of gears, a mannequin dressed like an Ottoman (he really missed an opportunity to call it an Ottoman-aton), and a chessboard.

It played against European royalty, Benjamin Franklin, and Napoleon Bonaparte. It could converse by spelling out words on a letterboard. It could recognize when moves were illegal. It had facial expressions. It could work in the dark.

And it could do all of that because it was a lie.

The cogs and gears that ran the Turk weren’t connected to anything. The whirs and clicks it made were for show. What made the Turk work was a human secreted away inside the base, working the machine like a puppet. Because the Mechanical Turk was a magician’s illusion.

This past week had its own Mechanical Turk moment. The X1 Neo is a $20,000 domestic helper robot. It can do anything around the house from folding clothes to vacuuming to loading the dishwasher at the blinding pace of three items every five minutes. Its movements are pretty clunky and slow, but what do you want from the first fully-autonomous robot servant?

Except, well, it’s not autonomous. In fact, for most of the video above, the X1 Neo was being piloted by a worker in a VR headset. And when the production units ship, you’ll have to schedule time with an operator to teleoperate your robot and do the tasks it can’t do on its own (which currently appears to be most of them).

Ideally, a robot’s on-board AI could learn to do these things. It turns out, AI is being taught to do real-world tasks the same way LLMs were trained — by exploiting human labor. Throughout developing nations around the world where labor is inexpensive, people are putting on smart glasses and doing tasks over and over in order to capture data that will be used to train robots to move in and interact with the real world.

On the one hand, at least they’re getting paid (unlike the writers whose work went into training LLMs — a group that includes all of us here at Rogue). On the other hand, gross.